Why Every Newborn Needs the Hepatitis B Vaccine: Countering the Selective Screening Myth

A comprehensive guide to understanding universal hepatitis B vaccination and why it protects all infants—not just those with infected mothers

The Inconvenient Truth Behind the Screening Argument

Every year, a recurring conversation surfaces in clinical settings, parent forums, and public health meetings: "Why should my baby get the hepatitis B vaccine if my mother's screening test came back negative?" It's a seemingly logical question. After all, if you've been tested and you don't have hepatitis B, why vaccinate?

The answer is far more complex—and far more compelling—than the screening test result suggests.

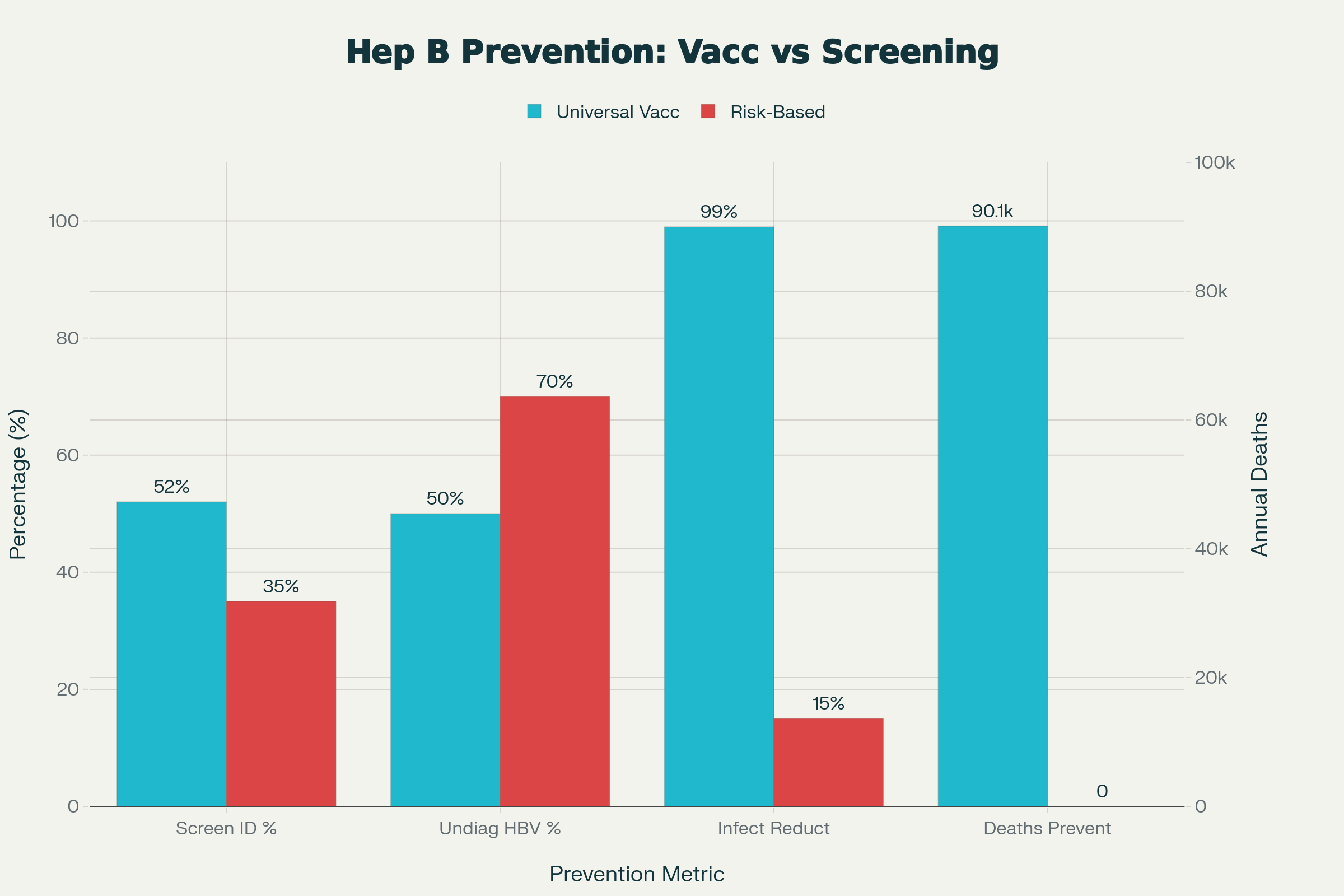

Since the CDC established universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination recommendations in 1991, chronic hepatitis B infections among children and adolescents have declined by an astounding 99%. But this remarkable success now faces an existential threat from proposals to abandon universal vaccination in favor of selective, risk-based screening. Understanding why this represents a dangerous public health miscalculation requires examining the evidence that decades of research has accumulated.

The Hidden Problem: Screening Isn't Foolproof

Not All Infected Mothers Are Identified

Let's start with a sobering reality: prenatal hepatitis B screening fails to identify a significant proportion of infected pregnant women. While screening is recommended for all pregnant women, implementation gaps persist. An estimated 16% of pregnant individuals may not be tested at all during pregnancy. Even among those tested, national data reveal that only 52.6% of infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers were actually identified through prenatal screening in 2017.

Think about what those numbers mean in practical terms. If screening identifies only about half of infected mothers, and 16% of pregnant women aren't even tested, we're leaving a substantial population of at-risk infants without identified protection.

The Window Period: A Silent Vulnerability

The timing of prenatal screening introduces another layer of complexity. Hepatitis B has an incubation period of 6-8 weeks—a window called the "window period" when someone is infected but the virus doesn't yet show up on standard blood tests. A pregnant woman tested early in pregnancy could acquire HBV a few weeks later and still test negative when the baby is born.

But by then, it's too late. The virus has been transmitted vertically to the newborn during delivery, and without immediate prophylaxis, a chronic infection may already be establishing itself in the infant's liver.

Laboratory Blind Spots

Standard hepatitis B testing, while generally reliable, has documented limitations. False-negative results can occur due to:

HBsAg mutations that evade detection by standard assays

Occult infections with very low levels of virus circulating in the bloodstream

Technical errors in laboratory processing

Timing mismatches between infection and testing

Expert reviews acknowledge that even with current screening programs, a 10% false-negative rate means substantial numbers of infected mothers go unidentified. In a country with approximately 3.6 million live births annually, a 10% false-negative rate means roughly 360,000 newborns could be born to mothers with undetected hepatitis B infections each year.

The Undiagnosed Epidemic: Half a Million Hidden Cases

A Staggering Gap Between Infection and Diagnosis

Here's a statistic that puts the screening limitation in stark perspective: approximately 50-70% of people with chronic hepatitis B are completely unaware they are infected. Globally, only 10% of the estimated 300 million people with chronic hepatitis B have been diagnosed. In the United States, an estimated 2.4 million people live with chronic HBV, but about half don't even know it.

This massive reservoir of undiagnosed infection has profound implications. Many of these individuals are parents, relatives, or household members of newborns. They're not reckless or negligent—they genuinely don't know they're infected. They weren't screened. Their infection was overlooked. Or they were infected after their screening.

A young father who contracted HBV years ago but never got tested. A sibling who acquired the virus through a partner and doesn't realize they're infectious. An extended family member visiting from a high-prevalence region who doesn't know their status. These are the real-world scenarios that universal screening simply cannot capture.

Age-Dependent Risk of Chronic Hepatitis B Infection and Long-Term Outcomes.

Beyond Mother-to-Child: The Horizontal Transmission Epidemic

Why Maternal Status Isn't the Whole Story

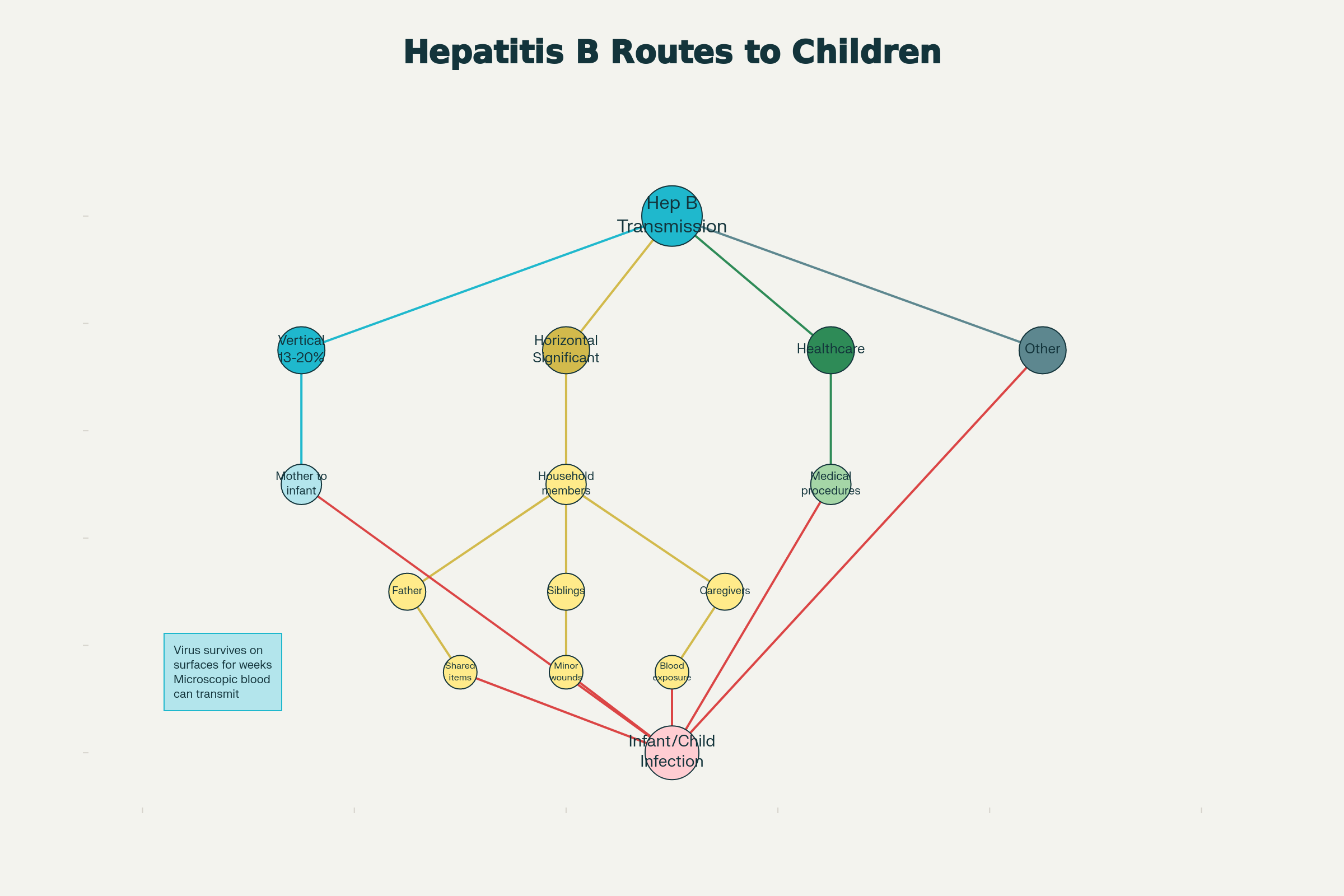

When we focus exclusively on maternal HBV status, we commit a critical public health error: overlooking transmission from other household members. Research reveals that vertical transmission from mother to infant accounts for only 13-20% of chronic HBsAg carriage in some endemic regions. Where, then, does the majority of infant HBV acquisition come from? The answer points directly to horizontal transmission.

Horizontal transmission—infection acquired from household contacts, caregivers, or other children—represents a significant and often-overlooked route of HBV acquisition during early childhood.

The Infected Household

Studies demonstrate that 27.2% of families have at least one HBsAg-positive member, creating abundant opportunities for horizontal transmission within households. Children can acquire HBV through surprisingly mundane exposures:

Sharing razors or toothbrushes

Contact with infected blood from minor wounds

Sharing items like hairbrushes or nail clippers

Microscopic blood exposure from skin lesions or mouth sores

The hepatitis B virus is remarkably persistent. It can survive on surfaces for weeks and transmit through microscopic amounts of blood that may not be visible to the naked eye. A child with a small cut on their finger touches a shared toy. A toddler puts a contaminated object in their mouth. A minor nosebleed leaves virus on a pillow that the infant is later laid upon.

Multiple Transmission Routes Create Risk for Unvaccinated Infants

The Data Tells a Troubling Story

Research examining horizontal transmission patterns reveals that HBV infection prevalence among children increases rapidly after infancy, reaching a peak among 5- to 9-year-olds in endemic regions. Family screening studies of children with chronic hepatitis B show that when maternal markers are excluded, horizontal transmission from fathers and siblings accounts for substantial proportions of pediatric infections.

In families with HBsAg-positive members, horizontal transmission frequently occurs through prolonged contact and shared living conditions, particularly in settings with lower socioeconomic status. These aren't rare circumstances—they represent the lived reality for millions of families globally.

An unvaccinated infant born to a screened-negative mother but living in a household with an undiagnosed HBsAg-positive parent has no protection against this route of transmission. The negative maternal test provides false reassurance while real risk lurks in the home.

The Age-Dependent Catastrophe: Why Infants Are in the Highest-Risk Group?

The 90% Rule: Infant Vulnerability

Here's perhaps the most critical statistic in this entire discussion: approximately 90% of infants exposed to hepatitis B during their first year of life will develop chronic infection.

To understand how extraordinary this number is, consider the contrast with age:

Infants (<1 year): 90% develop chronic infection

Children (1-5 years): 20-30% develop chronic infection

Adults: 5% develop chronic infection

This dramatic age-dependent difference reflects fundamental immunological principles. Neonates have immunologic tolerance mechanisms specifically designed to prevent maternal alloimmune responses. This immunologic immaturity, while evolutionarily protective, creates a dangerous vulnerability to viral pathogens.

When HBV enters an infant's bloodstream, it rapidly disseminates to the liver where the immunologically immature system cannot mount an effective antiviral response. The virus establishes itself before the immune system has the developmental capacity to clear it. What should be an acute, self-limited infection instead becomes a lifelong chronic infection.

The window of maximum vulnerability is the first year of life. Every month that an unvaccinated infant remains unprotected increases the probability that a chance exposure—from any source—will establish chronic infection.

The Prophylactic Window: Why Timing Is Everything

The 24-Hour Reality

The hepatitis B birth dose serves a function that most other pediatric vaccines don't: it acts as post-exposure prophylaxis for infants who may have been exposed during delivery or in the immediate perinatal period. This isn't primarily about disease prevention in the long term—it's about preventing immediate, acute exposure from becoming chronic.

When the vaccine is administered within 24 hours of birth to an infant exposed during delivery, it provides the immune system a time-sensitive opportunity. The vaccine stimulates antibody production and cellular immune responses that can clear the virus if exposure occurred recently, before it has time to establish chronic infection in the liver.

But this window closes rapidly. If a newborn has been exposed—whether from an undiagnosed maternal infection, a household contact, or a healthcare exposure—and vaccination is delayed to 2, 6, or 12 weeks of age, the infection will already be established and chronic by the time the first vaccine dose is administered.

Given the 90% chronicity rate for infant-acquired infections, this delay transforms a preventable acute exposure into a lifelong chronic infection with all its attendant morbidity and mortality.

Delaying vaccination isn't simply less effective than birth-dose vaccination. It's a qualitatively different intervention against a fundamentally different disease trajectory—acute recovery versus chronic infection.

The Long Road to Disease: What Chronic Hepatitis B Means for Infants

From Silent Infection to Silent Killer

An infant who develops chronic hepatitis B faces a silent progression that unfolds over decades. Unlike acute hepatitis, which produces symptoms, chronic HBV infection is typically asymptomatic during childhood and adolescence. Parents notice nothing wrong. The child appears healthy. School attendance is unaffected. Life continues as normal.

Yet underneath, viral replication continues relentlessly. The liver sustains ongoing inflammation. Fibrosis slowly develops.

The Statistics of Severity

The clinical trajectory of chronic hepatitis B acquired during infancy carries devastating long-term consequences:

25% of chronically infected individuals will develop cirrhosis

Once cirrhosis develops, annual hepatocellular carcinoma risk rises to 2-3%

Approximately 1 in 4 persons who became chronically infected during childhood will die prematurely from cirrhosis or liver cancer

To translate these statistics into human terms: Among 100 unvaccinated infants who become chronically infected with HBV, approximately 90 will survive to adolescence with seemingly normal health. But eventually, 25 of those 90 will develop cirrhosis. And 3 of those 25 will develop liver cancer each year they live with cirrhosis.

The Economic and Social Burden

Children chronically infected with HBV face more than just medical consequences. They face:

Lifelong medical monitoring with regular liver ultrasounds and lab work

Potential antiviral therapy with its own side effects and cost

Psychological burden of managing a chronic disease throughout their lives

Discrimination and stigma in educational and employment settings

Reproductive considerations regarding transmission risks

Economic impact including lost productivity and premature mortality

Research analyzing the cost of delaying the hepatitis B birth dose projects catastrophic consequences: at least 1,400 preventable infections, 300 cases of liver cancer, 480 preventable deaths, and over $222 million in excess healthcare costs for each year the revised recommendation remains in place.

Why Risk-Based Screening Has Always Failed?

The Historical Record

The United States and other countries have empirical evidence demonstrating the fundamental inadequacy of selective, risk-based hepatitis B vaccination strategies.

Prior to 1991, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended hepatitis B vaccination only for infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers and for high-risk older age groups. This selective approach consistently failed to control hepatitis B transmission. Experts recall that "we've tried risk-based approaches to vaccination before, and we saw persistently high levels of hepatitis B in children, young adults, and adults."

The Screening Paradox

The fundamental problem with risk-based screening is that it requires identifying and managing risk in advance. In practice, this has proven systematically impossible:

Unidentified risk: Known risk factors are present in only 35-65% of HBV-positive pregnant women. This means that even with careful screening protocols, the majority of infected individuals may not have traditional "risk factors."

Variable screening effectiveness: Studies examining risk-based screening found that restricting vaccination to identified high-risk groups missed substantial proportions of HBV infections. Selective screening based solely on immigration from high-prevalence countries identified 85-99% of infections in higher-prevalence clinical settings but missed approximately two-thirds of HBV infections in lower-prevalence practices.

Implementation failures: Even when risk factors are identified, implementation of appropriate interventions frequently fails. Only 52.6% of infants born to identified HBsAg-positive mothers received appropriate prophylaxis.

Hidden populations: Individuals with chronic HBV infection often have no identified risk factors. They contracted the disease years ago through routes they've forgotten or don't recognize as risky. They represent an unquantifiable population that risk-based screening simply cannot address.

Universal Vaccination vs. Risk-Based Screening: Why Selective Approaches Fail

The Vaccine: Safe and Effective Beyond Question

Three Decades of Safety Surveillance

The hepatitis B vaccine demonstrates an exceptional safety profile supported by more than 30 years of surveillance data and extensive research. Comprehensive reviews of over 400 studies spanning 40 years find no evidence that the birth dose causes immediate or long-lasting health issues.

Multiple large-scale studies confirm that the vaccine is not associated with:

Increased risk of infant mortality

Fever or sepsis

Multiple sclerosis

Autoimmune conditions

Sudden infant death syndrome

The most commonly reported adverse events are mild and transient—primarily crying and fussiness that resolve within hours. Severe reactions are rare.

This remarkable safety record reflects rigorous pre-licensure testing and continuous post-marketing surveillance involving millions of vaccinated infants globally.

Efficacy That Exceeds Clinical Needs

When administered within 24 hours of birth, the birth dose is up to 90% effective at preventing perinatal transmission from infected mothers. The complete three-dose series provides 95-98% protection, with protective antibody responses developing in approximately 95% of immunocompetent infants.

Long-term follow-up studies demonstrate that protection from the infant hepatitis B vaccine series extends for more than 35 years. A landmark 2022 study found that US children who received the vaccines as newborns were 22% less likely to die from any cause—a finding suggesting benefits extending beyond hepatitis B prevention alone.

The Success That Nearly Became Forgotten

Before and After

The dramatic decline in pediatric hepatitis B infections following universal vaccination implementation in 1991 represents one of modern medicine's greatest achievements. But this very success has created a dangerous blind spot.

The success of universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination has nearly eliminated a once-common childhood infection, creating a generation of healthcare providers and parents with limited direct experience of the disease's devastation.

Before the vaccine's introduction, hepatitis B took the lives of young individuals with tragic regularity, including cases of teenagers developing fatal liver cancer from infections acquired in infancy. Children died. Parents buried their children. The pain was real and undeniable.

Those tragedies now seem distant. The disease feels theoretical. The vaccine feels unnecessary.

By the Numbers

Yet the impact of that 1991 decision endures in measurable terms:

More than 500,000 childhood infections prevented

An estimated 90,100 childhood deaths averted

More than 6 million hepatitis B infections prevented

Nearly 1 million hepatitis B-related hospitalizations averted

6 million cases prevented through the current vaccination schedule

In 2021, only 17 reported cases of newborns contracting HBV from their mothers occurred among approximately 17,827 infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers. This isn't a coincidence. This is the consequence of a policy that has saved millions of lives.

Global Health Imperatives: The 2030 Vision

The WHO Elimination Strategy

The World Health Organization has established ambitious goals to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030, defined as achieving a 90% reduction in new infections and a 65% reduction in hepatitis B-related deaths compared to 2015 baseline levels.

Universal hepatitis B vaccination, including timely birth dose administration, represents a fundamental pillar of this elimination strategy. The birth dose coverage target is set at 90% by 2030—up from just 39% globally in 2015.

What Works: Real-World Examples

Countries that have implemented universal newborn vaccination programs have demonstrated dramatic reductions in chronic HBV infection rates. The United States is now considered "an envy of the world because we have been able to" nearly eliminate childhood hepatitis B.

China's experience demonstrates that HBV vaccination combined with comprehensive prevention strategies reduced HBV-related deaths for acute hepatitis, cirrhosis, and chronic liver disease by substantial margins. Global data on hepatitis B elimination progress underscore the critical role of universal infant vaccination.

Addressing the Core Question: Why Vaccinate if Mom's Negative?

Let's return to the original question with eyes opened to the fuller picture:

The Problem with Selective Vaccination

Screening misses 10-50% of infected mothers through false negatives, timing issues, and implementation failures

Approximately 50-70% of infected people don't know their status, meaning an undiagnosed parent in the household could be infectious

Horizontal transmission from household contacts accounts for a large proportion of pediatric infections, not just maternal transmission

The 90% chronicity rate in infants means any exposure during the first year of life likely becomes chronic

The prophylactic window closes within 24 hours—delaying vaccination to confirm risk means the infant may already be chronically infected

Risk-based screening has historically failed when actually implemented; countries that used it saw persistent high rates of hepatitis B

The Answer

Universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination protects infants in several ways simultaneously:

From undiagnosed maternal infection that screening failed to detect

From household members with undiagnosed HBV that won't be identified until years later

From the 90% risk of chronic infection if exposure occurs during the vulnerable first year

From the transformation of what could be acute exposure into lifelong chronic disease

From decades of silent liver damage progressing toward cirrhosis and liver cancer

A maternal screening result showing negative status provides valuable information—but it doesn't eliminate the need for vaccination. It simply confirms one data point at one moment in time. It doesn't account for household contacts. It doesn't guarantee the test was accurate. It doesn't change the fundamental biology of infant vulnerability.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Advocating for selective vaccination based on maternal screening status sounds logical, rational, and efficient. It appeals to our desire for precision medicine and targeted interventions.

But it ignores the reality that precision medicine cannot be selective when half the target population doesn't know they belong to it. You cannot selectively vaccinate infants at risk if you don't know which infants are at risk.

The evidence from decades of epidemiologic research, public health practice, and clinical surveillance conclusively demonstrates that universal vaccination works where selective vaccination fails. That's not a theoretical projection. That's documented history.

Final Word: A Matter of Timing

Every newborn faces some risk of hepatitis B exposure during their critical first year of life. That risk comes from multiple sources that cannot be perfectly predicted or controlled. The infant's immune system's extraordinary vulnerability—the 90% chronicity rate—means that even a single exposure could establish lifetime infection.

The hepatitis B vaccine given at birth is inexpensive, extraordinarily safe, provides protection for more than 35 years, and offers prophylactic benefit during the critical window when infants are most vulnerable.

The question isn't whether a negative maternal screening test means your baby doesn't need the hepatitis B vaccine. The question is: why would you leave your infant vulnerable during their highest-risk period when a safe, effective, inexpensive prevention strategy exists?

The answer, supported by decades of evidence and millions of protected infants, is clear: all newborns should receive the hepatitis B vaccine at birth. Not because their mother has hepatitis B, but because all infants deserve protection from a preventable infection that can silently progress to liver cancer and premature death.

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Chapter 10: Hepatitis B. In Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Clinical overview of perinatal hepatitis B. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-b/hcp/perinatal-provider-overview/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Hepatitis B perinatal vaccine information – For providers. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-b/hcp/perinatal-provider-overview/vaccine-administration.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Screening and testing for hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recommendations and Reports, 72(10).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Protection against viral hepatitis: Recommendations of the immunization practices advisory committee. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Beasley, R. P. (1995). Importance of perinatal versus horizontal transmission of hepatitis B virus in the etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut, 38(Suppl. 2), S39–S42.

Chen, D. S., Kew, M., & Papatheodoridis, G. V. (2018). From infancy and beyond… ensuring a lifetime of hepatitis B virus prevention through vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(5), 1203–1213.

Hepatitis B Foundation. (2025). Why we give hepatitis B vaccines to infants. Retrieved from https://www.nfid.org/why-we-give-hepatitis-b-vaccines-to-infants/

HepVu & Public Health Partners. (2025). New analysis shows delaying the hepatitis B birth dose may lead to thousands of preventable infections and deaths. Retrieved December 2, 2025, from https://hepvu.org/news-updates/

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. (2025). Why hepatitis B vaccination begins at birth. Retrieved from https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2025/why-hepatitis-b-vaccination-begins-at-birth

Leuridan, E., Van Damme, P., Kкоординате, S., Schillie, S., Onorato, I., & Zanetti, A. R. (2014). Duration of protection after infant hepatitis B vaccination series. Pediatrics, 133(6), e1500–e1509.

Lok, A. S. F., Gupta, S., & Fung, S. K. (2024). Hepatitis B virus–related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, burden, and prevention. NIH/NCBI Publications.

National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. (2025). Why we give hepatitis B vaccines to infants. Retrieved from https://www.nfid.org/

Papatheodoridis, G. V., Lampertico, P., Schillie, S., & Miele, L. (2023). Hepatitis B virus as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

Schillie, S., Vellozzi, C., Reingold, A., Harris, A., Haber, P., Ward, J. W., & Nelson, N. P. (2018). Meeting the WHO and US goals to eliminate hepatitis B infection by 2030: The importance of timely birth dose vaccination. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 218(Suppl. 3), S135–S144.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2009). Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: Recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150(12), 874–876.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2020). Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: Screening. JAMA, 324(24), 2415–2422.

Van Damme, P., Leuridan, E., & Zanetti, A. R. (2016). Long-term protection after hepatitis B vaccine: 30-year follow-up data. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 214(1), 1–3.

World Health Organization. (2025). Hepatitis B. Fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b

World Health Organization. (2020). Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016–2021: Towards ending viral hepatitis. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/hepatitis/elimination-of-hepatitis-by-2030

World Health Organization. (2020). Elimination of hepatitis by 2030. Policy framework. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/hepatitis/elimination-of-hepatitis-by-2030

About the Author

Felix E. Rivera-Mariani, Ph.D., FAAAAI is a distinguished biomedical researcher, educator, and public health advocate with expertise spanning biochemistry, microbiology, immunology, environmental and respiratory health, and computational approaches. A fellow of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (FAAAAI), Dr. Rivera-Mariani is committed to bridging the gap between rigorous scientific research and accessible public health communication. Learn more about Dr. Rivera-Mariani here!